The Next Horseman of the Apocalypse is a Chicken Jockey

Now I watched when the Lamb opened one of the seven seals, and I heard one of the four living creatures say with a voice like thunder, "Come!" And I looked at Jack Black, and behold, CHICKEN JOCKEY!

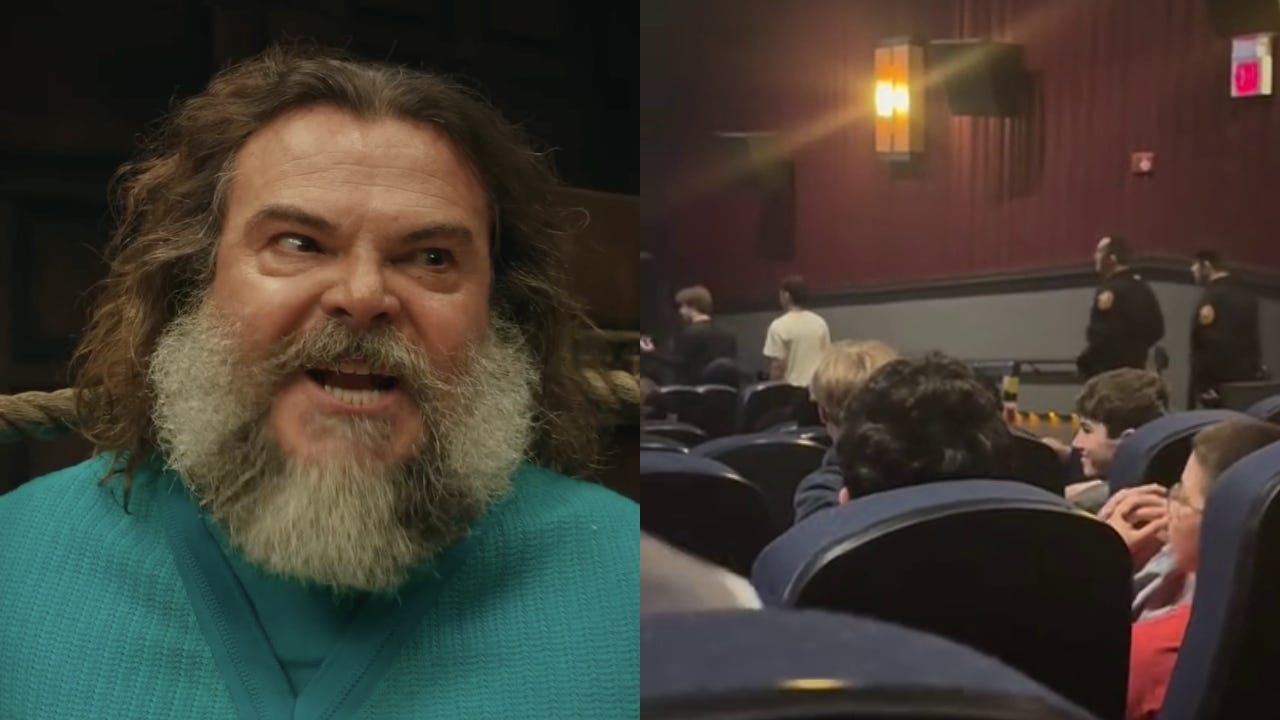

The Minecraft movie came out this April. You ever play the game? You probably have, or at least, know a younger person who has. Midway through the film, actor Jack Black (playing the hero, Steve) bellows the phrase “Chicken jockey!” on screen – a reference to the game where a baby zombie may arrive riding a chicken. Something about the utterance drove the audience to madness. Some real heart of darkness sh**t.

Literally jockeying on eachother’s backs, kids leapt from their seats, screaming the line, flinging popcorn around like confetti, and cheering for that climactic moment where they are gathering maximum attention. For a moment, the cinema becomes an extension of the sandbox chaos of Minecraft itself, a place where basic etiquette doesn’t apply. Jack Black has since personally entered a cinema in the states and said “For today’s presentation of A Minecraft Movie, please no throwing popped corn, no lapis lazuli and also absolutely no chicken jockey!”

This behaviour shows the extent to which technology has driven reckless and concerning behaviour in young adults. This TikTok-fueled craze, seen with other franchises, has been turning otherwise polite movie showings into raucous, sometimes even dangerous events.

Videos flooding social media captured crowds of adolescents primed to act completely bananas at the iconic chicken jockey reveal. Yet this is only scratching the surface behind what has happened here. Young adults live in a dimension of simulacra where reality becomes a playground for digital media to bleed into. Their hero’s journey plays out not in the waking lives, but in the virtual one.

Attributing Minecraft to the status of a mere game misses something you can only derive from firsthand experience of it. Each block of the world is generated based on some procedural code, to make it coherent, full of biomes, animals, dungeons. But while most games feel narrow, or vacuous, Minecraft has a way of settling players into this relaxing, almost liminal feeling, like a simulation of our reality that our minds are content to reside within, with its gentle ambient music and repetitive tasks. There is intrigue and even an uncanny quality to it too, activating the imagination of young people. Horror is a major theme of popular services and assets in Minecraft and Roblox.

In Britain, several cinemas posted stern warnings at their doors, threatening to evict anyone who joins in the TikTok trend of disruptive yelling and stunts during A Minecraft Movie. “Any form of antisocial behaviour… such as loud screaming, clapping and shouting will not be tolerated,” read one notice at a Cineworld in Oxfordshire, adding that offenders *“will be removed from the screening and not entitled to a refund”*. A Reel Cinemas location similarly vowed to eject rule-breakers and even involve police *“where necessary”*. In New Jersey, one theater went so far as to ban unaccompanied minors altogether after an “unfortunate situation” in which “large groups of unsupervised boys engaged in completely unacceptable behaviour, including vandalism” on opening night. Management at that cinema bluntly urged parents to talk to their sons about how they’d behaved. The reports from some screenings sound utterly wild. One stunned moviegoer in Wales likened the theater to a zoo, remarking, *“Quite honestly I’ve seen monkeys at Chester Zoo behave more civilised than those at the 1:45pm showing on Saturday.”*

Back in 2022, a TikTok trend called #Gentleminions encouraged teenagers to attend Minions: The Rise of Gru in formal suits and ironically over-the-top enthusiasm. Groups of well-dressed Gen Z-ers descended on cinemas, cheering and clapping for the Despicable Me spinoff so loudly that some UK theaters actually banned unaccompanied teens in suits from screenings. Interestingly, Cineworld’s UK chain cleverly tried this: they announced one-off Minecraft showings where fans could dress up and “let your hair down,” openly encouraging shouting “CHICKEN JOCKEY!” to get it out of their system. What started as a tongue-in-cheek meme became so prevalent that theater chains had to adapt on the fly. The Minecraft movie craze is a level up from that: more organic (these kids aren’t in suits or disguises; they’re genuine fans) and far more unruly. One commenter wryly dubbed the Minecraft movie “Gen Z’s Rocky Horror”, alluding to the 1975 cult film whose midnight showings famously involve audiences shouting lines and throwing objects at the screen. The comparison isn’t perfect – Rocky Horror Picture Show audience participation is a long-running, organized tradition, whereas the Minecraft mayhem is spontaneous and social media-driven – but the spirit is similar. Today’s young viewers have crafted their own interactive ritual, turning a mainstream blockbuster into a participatory communal event.

Online, the commentary is split. Many young people and parents celebrate the rowdy screenings as “so much enthusiasm” and harmless fun. One parent in Australia described a theater full of 13- to 15-year-old boys joyously clapping and whooping at every in-joke and cameo, declaring “Movies are back!” as she watched her kids revel in the moment. “The crowd was fairly well behaved, no one was swearing, or throwing popcorn or any other shenanigans,” she wrote, calling it “a little mean-spirited” that a few grumpy adults complained to staff about the noise. Other parents chimed in to agree that the collective glee was infectious and even “wholesome,” noting that seeing teens cheer for their favorite game brought to life was *“just so happy for them”*. In an era when critics gave the Minecraft movie overwhelmingly negative reviews for its artistic merits, these fans managed to alchemize a “terrible” movie into an unforgettable experience simply through sheer collective excitement.

Yet plenty of observers (especially those outside the target demographic) found the trend juvenile and irritating. To them, a movie theater is not a Minecraft server – it’s a place to quietly watch a film. “It’s a movie, not a sports game,” one annoyed commenter scolded, arguing that cheering throughout is “really inconsiderate” to people who just want to hear the dialogue. Others insisted “clapping and cheering don’t belong during a movie” unless perhaps at the very end. To these critics, a rowdy Minecraft screening “sounds like a nightmare” and betrays a generation that doesn’t respect boundaries. The phrase “feral” has even been tossed around on social media to describe Gen Z and Gen Alpha kids these days – half-jokingly painting them as a pack of wild creatures raised on YouTube and let loose in civil society. (One trending quip: “Gen Alpha is feral, and they will destroy us with a million tiny skibbidi toilets. No cap.” – a sardonic reference to a popular absurdist meme among kids.) It’s the classic culture clash: youthful exuberance and internet-fueled humor bumping up against traditional etiquette. And in the case of the Minecraft movie, that clash played out in real time, sticky theater floors and all.

Why are kids acting out like this – and why now? A big part of the story is the psychology of youth in the social media era. Today’s tweens and teens are the first truly “born digital” generation, raised on Minecraft and YouTube, TikTok and Twitch. For many of them, the line between being an audience and being a creator is blurry. Nearly 30% of kids aged 8 to 12 say their number one career goal is to become a YouTuber or online content creator. In other words, a huge chunk of this generation doesn’t just consume media – they instinctively look for ways to perform, participate, and broadcast. So, when a bunch of Minecraft superfans pack into a theater, it’s almost second nature for them to see it as a two-way experience. Watching the movie simply isn’t enough; they feel compelled to make their own content out of it – hence the sea of phones held aloft to record that perfect TikTok moment. The Minecraft movie trend essentially turned the theater into a stage, and the kids into the stars of their own viral video.

Psychologically, teenagers are also wired to push boundaries and seek peer approval. The adolescent brain is still developing its impulse control and risk assessment, but the reward centers tied to social validation are in full gear. Studies show that teens are “particularly vulnerable to social pressure” – if they see a behavior getting likes and laughs, they’re more likely to copy it. So when TikTok clips of “chicken jockey” chants blew up with millions of views, it set off a feedback loop: more kids felt emboldened to do the same, or even escalate the stunt, to get a piece of that attention. There’s a FOMO element too – nobody wants to be the only dull kid in a theater of screaming fans. In a sense, it’s crowd psychology meets algorithmic amplification. One kid’s goofy outburst becomes another kid’s idea of a challenge to top. Throwing a bit of popcorn in the air for the camera might earn some digital clout; so why not throw an entire tub? After all, the likes will disappear in a day, but a legendary prank story could live on in their friend group forever.

It doesn’t hurt that Minecraft as a game practically celebrates mischief and creativity. This is the generation that spent their childhood building digital worlds with friends, where chaotic experimentation is half the fun. In Minecraft, you can construct a castle or blow it up with TNT; you can cooperate or playfully troll your buddies. The culture around the game – and its massive community on Twitch and YouTube – skews towards a kind of playful anarchism. Think of the famous Minecraft videos where YouTubers shriek in mock horror or triumph; that exaggerated energy is infectious. Many of today’s 13-year-olds grew up watching streamers react with theatrical flair to every creeper explosion or rare Easter egg. It’s no wonder the sight of a “baby zombie riding a chicken”, a silly rarity in the game, made them lose their minds in the cinema. The movie was giving them, in real life, the kind of moment they’d normally share and react to in a game or stream. So they responded in kind – as if they were live on stream themselves, hamming it up in front of an audience of peers.

The chicken jockey is an inside joke that only the initiated get, and by exploding with applause they signal their membership in the Minecraft generation. There’s a powerful feeling of community and belonging in that synchronized chant. Strangers in the theater become friends simply because of the mutual understanding. Internet culture can turn performative and even toxic when clout is on the line.

Cultural critics have noted that today’s youth are in some ways performing life for an invisible audience. Sociologist Erving Goffman long ago described everyday social interactions as theatrical performances, and social media has cranked that to 11. For Gen Z and Gen Alpha, “pics or it didn’t happen” isn’t a joke; it’s a guiding principle. Experiences gain meaning by being captured and shared. So from that perspective, a movie isn’t only a story to consume – it’s a backdrop for your story, a prop in your content. The Minecraft movie was a perfect storm: a pre-made meme, a young fanbase, and a hyper-connected network to amplify it all. It’s a fascinating feedback loop of internet culture feeding into real life, and then real life feeding back into internet culture. Or, is the start of a new trend where fiction begins to spill into and distort reality?

As the popcorn settles, we are left with a tricky question: how do we allow kids today to experience an event that excites them, that will give them core memories like we have, while still directing them and restricting antisocial behaviour.

On the flip side, some worry that accommodating these trends just rewards bad behavior. There were slurs (including racist remarks) uttered, receiving hollers and cheering, showing a segment of youth culture who not understand the effect of this language. If we say “kids will be kids” and let them go ape, do we set a precedent that public norms don’t matter? This concern has led theaters to enforce those zero-tolerance policies, and even arrange special “rowdy screenings” segregated from the regular ones. (while imploring them not to go “full creeper” with actual mess or mayhem.) Such measures acknowledge the phenomenon but aim to channel it more responsibly. It’s a bit like offering a mosh pit section at a concert: have your fun, but over there, on your own terms.

Underlying these debates is a broader truth: youth culture has always unnerved older folks. Today’s memes and TikToks are yesterday’s rock-n-roll and comic books – new forms of expression that seem foreign and disrespectful until they eventually become mainstream (or the kids grow up). That doesn’t mean every viral trend should be celebrated – certainly not ones that lead to dangerous acts – but it helps to understand where it’s coming from.

There’s a sharp insight in that rant. In a world that often feels “f**ked up” maybe we shouldn’t be so quick to crush a bit of innocent joy – even if it’s loud and messy. The Minecraft kids weren’t out hurting anyone intentionally; they were reveling in something together. That kind of unbridled communal joy has been rare in recent years. It’s worth noting that despite the hand-wringing, A Minecraft Movie has been a smash hit, breaking box office records for a video game adaptation and injecting much-needed life into cinemas. Still, society’s reaction to the movie is concerning. The behaviour is like that of a swarm. Learn how to prepare for it here.