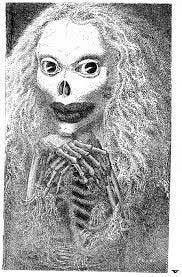

Those Who Dwell in Life-In-Death

Do we ever truly die? Is life and death binary? For some things, the answer is not as simple as yes or no.

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

Her locks were yellow as gold:

Her skin was as white as leprosy,

The Night-mare LIFE-IN-DEATH was she,

Who thicks man's blood with cold.

- Samuel Coleridge

Are death and life really opposites?

After all, the death of one is the source of life for another. Even in our limited and narrow sense of what we are as living beings, we must conclude that we are essentially a wave of genes. Such genes carry on long after we, as a singular vessel, dissipate. Maybe it’s not death that we encounter at the end then, but change. Every form of life that preceded us also carries on in service of new life. A mother’s death is accelerated by the presence of her offspring. In religion, this theme is neigh omnipresent, of sacrificing oneself so that posterity may survive. Yet some stand right on the precipice of life and death.

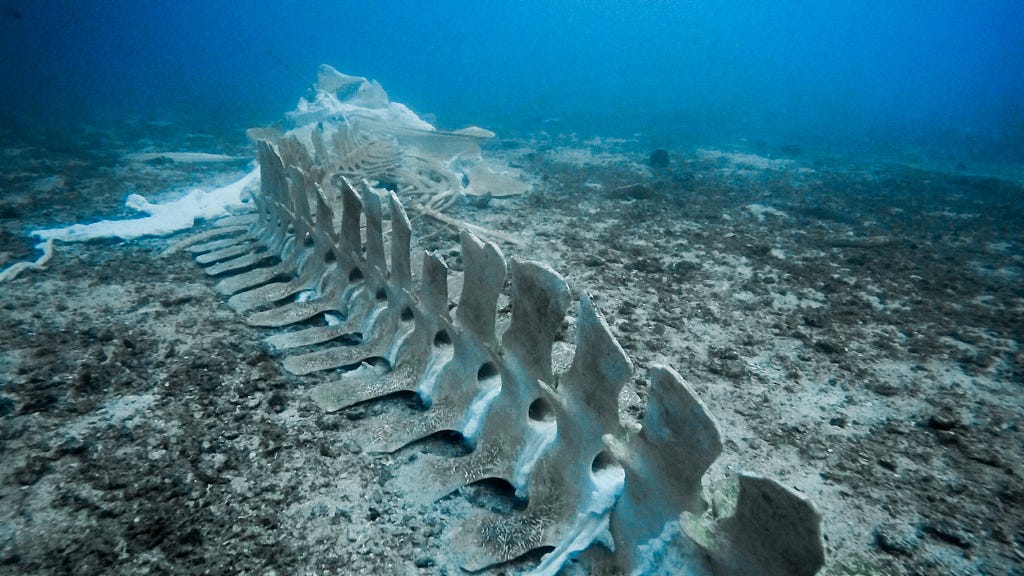

In some of the deepest recesses of the ocean, nutrients are scarce. When the whale dies and her lungs deflate, she plummets to the floor. The coldness of that remote part of the ocean slows down the decay and the high pressure allows her to fall intact and sink to even greater depths. A whale’s corpse, falling to the bottom of the sea, creates an entire ecosystem that supports deep-sea organisms for over half a century.

All sorts of flora and fauna colonize the dead whale. Over four hundred species, actually. From octopus, giant isopods, squat lobsters, polychaetes, prawns, shrimp, lobsters, hagfish, Osedax, crabs, sea cucumbers, to sleeper sharks. The mollusks and crustaceans dine on its calcium to support their shells. Meanwhile, bacteria and fungi secrete enzymes, breaking down protein from the bones. Some species of mussels, limpets and worms even depend entirely on whalefalls to exist. As the seawater dissolves the bones, the release of phosphorus gives an energy currency to all living cells around it. Afterwards, her skeleton becomes something of a coral reef.

Both the whale’s bones and blubber are rich in lipids, which are really concentrated energy stores. The release of liquid from decaying lipids attracts scavengers from great distances. Later, these lipids release sulfides that nourish bacterial production, forming the base of a food chain that sustains manifold organisms for decades upon decades to come. The way we, as humans, use lipids, reveals a kind of reverence towards death. Not only do we use lipids to preserve corpses, but it’s also lipids that make cremation possible: heat consumes the soft tissue, leaving behind only ash. Of course, we can’t forget that the candles we use for funerals and memorials, are also made of lipids. For millennia we have used lipids directly from whale cadavers.

It’s not just whales that have given Life-in-Death. Think back to the age where mammoths, giant ground sloths, the woolly rhino, terror birds, the giant dear and Irish Elk, roamed the Earth- before we killed them off. Such old gods as these made an incomprehensible contribution to their ecologies. We know today that dead whales are custodians for deep-sea biodiversity. They are a biome in and of themselves. It’s insane to imagine how important such biomes were, some five million years ago, when the biggest whales alive were double the weight of the heaviest ones we have today. Our ancestral species likely survived because of the energy and nutrients released by these colossi.

All the gifts of the whale’s death creates a festival ground for a menagerie. One of its members, the hagfish, surfaces to mind the image of a banshee. A corpse dweller, is the hagfish, slipping even further across the frontier behind life and death. She hosts a unique elixir that keeps her fluid, allowing her to move freely through the labyrinth of a decaying body. They eat their prey from the inside out. Their skin has a strange ability to absorb dissolved organic matter almost as if they were designed to eat dead or dying creatures by simply resting inside them. Their mouths are coated in writhing tentacles like an eldritch monstrosity.

The whale, when it dies, is no longer a living whale. It has died. Other creatures, though, cannot be quite as clearly certified as dead or alive.

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die.- Abdul Alhazred

In the case of the Children's python, females can retain undeveloped eggs or unfertilized ova within their oviducts for several years, potentially up to four years or more. During this time, the retained eggs or ova remain in a state of suspended development, leaving them bound in mother’s umbra. Extreme conditions, like droughts, may have caused this necessity. By retaining the eggs or ova, the female Children's python can essentially "pause" reproduction until more favorable conditions arise, increasing the chances of successful reproduction and offspring survival.

When environmental conditions become suitable, the retained eggs or ova can be ovulated and fertilized (if unfertilized), allowing the female to proceed with the normal process of pregnancy and giving birth to live young, as Children's pythons are ovoviviparous (giving birth to live young rather than laying eggs). Still, this is merely a frozen egg, rather than a fully-formed being with memories or any sense of agency. What else lies out there that can truly be said to exist in Life-in-Death?

The wood frog is essentially dead for long periods of winter. Like the whale, the frog exists in a state of suspension where organisms thrive on its body. With the frog, though, it’s only a quasi-cadaver, and will return back to life when the sun shines once again. With neither a heartbeat nor a breath, it survives only because its body produces large amounts of glucose, which acts as an antifreeze—keeping water liquid in the cells. Ice forms only in the spaces between the cells. Populating this frog while it’s in this state is a variety of lifeforms, including psychrophilic bacteria, fungi (again breaking down lipids), tardigrades, rotifers and nematodes.

In unfavorable environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, lack of water, or lack of oxygen, tardigrades can enter a state of cryptobiosis, where their metabolic activity is reduced to an almost undetectable level. In this state, they can survive for decades, or even centuries, without food or water.

During cryptobiosis, tardigrades enter a lifeless-looking "tun state" by losing almost all of their body water. In this remarkable state, they can endure extremes of temperature from near absolute zero at to scorching 151°C (304°F), the vacuum and intense radiation of space, massive pressures both high and low found in the ocean depths, and over a decade of dehydration.

When favorable conditions return, tardigrades can revive from their cryptobiotic state, rehydrating and resuming their metabolic processes and active life. It’s also possible that tardigrades produce specific proteins that help stabilize their cells and prevent damage during desiccation. They also have the ability to repair damaged DNA when they revive from cryptobiosis. Tardigrades and nematodes are both found in both whalefalls and wood frogs, perpetuating Life-in-Death in a completed cycle.

Whales die but create coral reefs. Snake eggs, wood frogs, nematodes and tardigrades can enter a suspended state and come back into animation thereafter. There’s also a species of jellyfish that reverses its own aging. Perhaps there’s a myriad of omitted creatures that exist in a kind of semi-immortality, or, as we’ve described it, as candidates for those who dwell in Life-in-Death. None, however, come as close to the case we’re coming to next. To be frank, it gives me the heebie-jeebies every time I think about it.

Insects can come to Life-in-Death when they are infected by the spores of the Ophiocordyceps. This fungus grows inside of the insect, consuming non-vital tissue, before working its way up to controlling its very behaviour and muscle coordination. Sometimes it will make the insect, usually an ant, leave its colony to climb up a tree, before making it jump to its death.

To begin, the fungus grows inside the host, consuming non-vital tissues. As it grows, the fungus produces chemicals that can alter the host's behavior and muscle coordination. In the final stages, the fungus causes the infected ant to leave its colony and climb up a plant stem or tree trunk. It makes ant climb high so that when it dies spores have maximum spread. The fungus induces a death grip, causing the ant's jaws to lock onto the plant material before it dies. From the ant's body, the fungus sprouts a long fruiting body which releases infectious spores to find new hosts.

As a child I was once confined into our house on the farm during a plague of mad cow disease. The Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or mad cow disease, involve the misfolding of proteins, leading to the accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates that can cause neurodegeneration and later, death. That brings us to the final stop in our journey across limbo, where we need to ask of ourselves, what does it mean for a person to have Life-in-Death?

But first thou must rend the garment that now thou wearest,

the attire of ignorance,

the bulwark of evil,

the bond of corruption,

the dark prison,

the living death,

the sense-endowed corpse,

the grave thou bearest about with thee, the grave, which thou carriest around with thee, the thievish companion who hateth thee in loving thee, and envieth thee in hating thee… that thou mightest not hear what thou must hear, and see what thou must see- Rudolf Bultmann

The mind, in a sense, can die even while the body lives on. The psychologist-philosopher Laing posited that in such disconnected states, the body is experienced as an alienated object rather than the subjective ground of being-in-the-world. The inner self becomes detached from the outer self, it becomes phantasized and volatile, and eventually decays. Describing the actions of one of his patients, where this creation of a form of death within life seemed to afford within itself a measure of freedom for anxiety. Being alive requires an active, even creative, reciprocation with others and the world. Inverting the concept of Life-in-Death, Laing refers to this phenomenon as Death-in-Life.

Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Heidegger explored the concept of "spiritual death" — a loss of meaning, purpose and authentic engagement with one's existence. Husserl and Merleau-Ponty, spoke of the possibility of “morte metaphysica" — a state where one loses the foundational sense of being and existential rootedness, leading to a kind of living death. Others, however, quite literally believe they are dead: those suffering from Cotard’s syndrome.

The stages of Cotard begins with the germination stage: psychotic depression and hypochondria. Next, the blooming stage begins, where the patient has delusions that negate their own existence, or the existence of the world. Afterwards, the depressive symptoms may appear to recede, but the delusions of them being dead do not.

Their brains reflect something of the decay associated with the moribund. The dysfunction of the frontal lobes, damaged parietal regions and other parts of the brain that regulate dopamine, serotonin and glutamate — all of this diminishes both the emotional and physical life of the person with this bizarre affliction.

Ultimately, we are ecological entities, whatever our mental, neurological or even spiritual make-up. We are not defined by our space or even time, but rather, in our relation to the others around us and our environment. Each and every person we meet can be influenced by us, in a small or big way. This compounds, cascading the influence across every person that they meet in turn. Our deaths do this, too. As individuals, our lives have a small impact, but as martyrs, we become more like a whalefall in a sea of deep-dwelling inhabitants. Most of us will carry on through genetics, and some, like Genghis Khan, have over 16 million people carrying his genes. It’s not so much that we live or die, but that our memories always are flowing across space and against the tide of time.

Death gives life an aim, then. It’s a directing, accumulation and centralization of energy, whereby the release of this energy, a scattering, allows a diverse range of organisms to feed and thrive. I only hope that when it comes for my time to die, that my scattering, be it through materials I share or through thoughts and inspiration alone, goes far and wide.

The Program is ZETT Announced Annual CCõnference HAILED in Washington Colleges FOR STUDENTS OF ALL CAPS 🧢